British history during the reign of Queen Victoria. The workshop of the world, the British Empire, the extension of the vote, the Great Hunger in Ireland. Queen Victoria and her family.

Transcript

DownloadMark

Hello and welcome to the podcast English for Life in the UK. This week, we're going to focus on the Victorian Age. So we're looking again at some British history and this time we're going to look at the period when Queen Victoria was on the throne. She was the British monarch, at this time. And I 'm joined today by John and Sheena. John - how are you today?

John

I'm very well Mark. Hello, Sheena, Hello Mark.

Sheena

Hello John. Hello Mark.

Mark

Hi - how are you, Sheena?

Sheena

I'm fine, thank you. And it's a lovely sunny day in Calderdale, for a change.

Mark

It is. It is. Definitely the spring is arriving - you can feel it, can't you? That spring's on its way. We're probably going to do an episode about the seasons and the weather, in the near future, so you can look out for that one.

So, we are looking, as I said, at the Victorian age. So, Queen Victoria was on the throne from 1837 to 1901 and at that time and, in fact, until our present Queen, she was the longest-serving monarch that we'd ever had in this country. That was a period where an awful lot was happening and we've covered some of those things in other episodes, so I'm going to start with just an overview and I'm going to link it to some of our other episodes. And then we're going to focus ... Sheena 's going to talk to us a bit about Queen Victoria herself and her family. And John's going to focus on an event during this period, to do with the Irish potato famine and what happened to the Irish people. John himself has an Irish passport, so he has a particular interest in that subject.

So, well, last week, we were talking about the Industrial Revolution, those of you who listened, and you may recall that at the end of that period, we were already in this Victorian age and by that time, Britain was known as "the workshop of the world". We were producing more goods than anyone else in the world, during the middle part of the nineteenth century. In fact, we actually produced over half of the coal, the iron and the cotton cloth produced, in the entire world. So here's this little island, producing more than anybody else was, at that time.

And John, last week, talked about the Great Exhibition, which was an exhibition where we showed off some of the things that we were producing in this country, and we were trading with large parts of the rest of the world. It was also a time when the transport systems were developing rapidly and particularly, the railways, so that all over this country but also increasingly, as the Victorian age continued, elsewhere, in the rest of the world. It was railways that were revolutionising the way in which people and goods could be moved around.

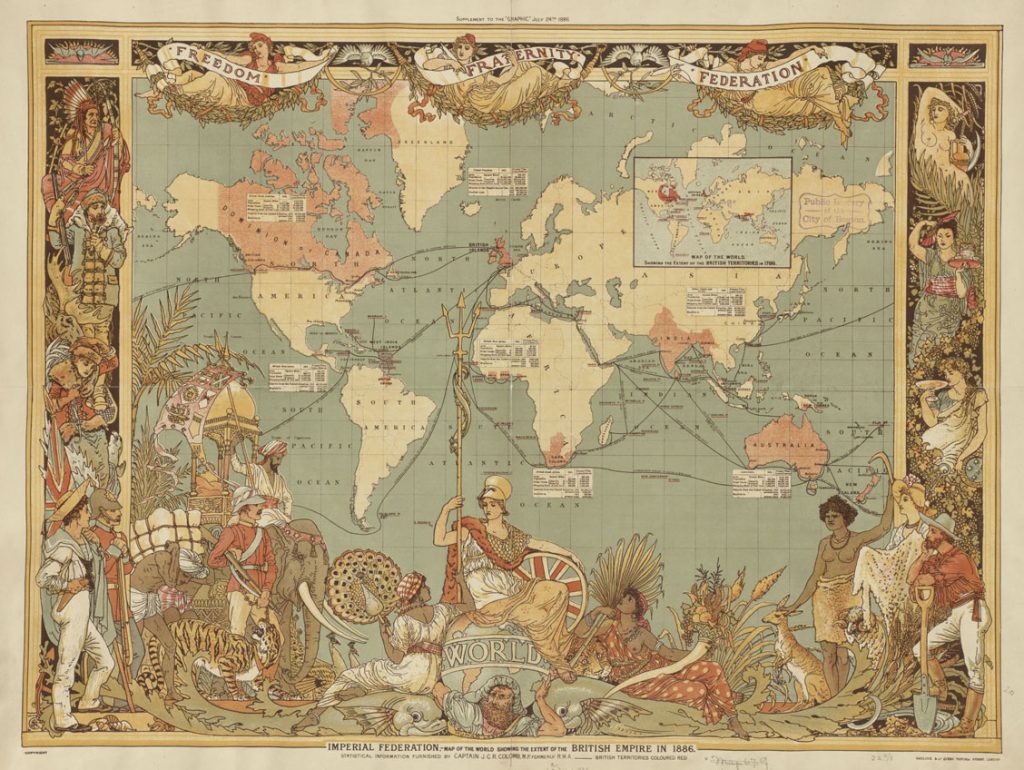

And that brings us to a second, really key thing about this period and that was the British Empire. Now, we covered that in more detail in episode 3 of this podcast - so if you want more detail on this, go back and find episode 3 of season one, of the podcast, to find much more detail about that. But the key thing is that Britain had gone out and had colonised large parts of the rest of the world. In fact, by the end of the Victorian period, there were 400 million people around the world who were in the British Empire. That means: they were ruled by Britain and Queen Victoria was their Queen.

In fact, a quarter of the world's land surface was in the British Empire, at its height. So this development of the British Empire happened particularly under Queen Victoria's rule and she became in fact, the first Empress of India, because India was a key part of our Empire. But the Empire stretched as far as Australia, large parts of Africa and, as I say, India and what is today also Pakistan and Bangladesh. And of course, with that Empire, that went, there was quite a lot of movement of people.

There were British people who went out and settled in the Empire - and often lived their whole lives out there - and there are still people who live in other parts of the world whose origins are British, from that period. But also, people started to come over from the Empire, and from other countries as well, to actually live in Britain, at that time.

(5 minutes: 33 seconds)

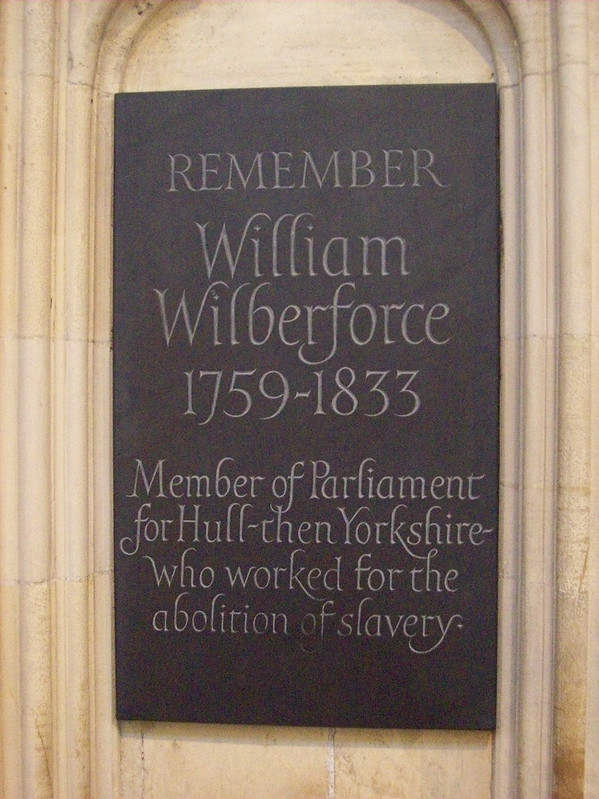

And you may recall, if you listened last week, that we were talking about the really shameful period of the slave trade, but when we get to the Victorian period, we do get the abolition of the slave trade. And whilst Britain should rightly feel responsible for some of the dreadful treatment of slaves and the thousands and thousands of slaves, died on the journeys and were clearly treated terribly for the rest of their lives, Britain actually was the first country - I think the first country in the world - to abolish slavery, officially. That happened right at the beginning of Victoria's reign and after that, we did play some role in bringing the slave trade to an end.

John

A lot in our region as well, Mark - probably the most famous abolitionist - as they were called - was a man called William Wilberforce, who was from Hull in Yorkshire, and I think we touched briefly the other week on a lot of the organised working-class in the cotton industry in the North West and in Yorkshire, were very firmly opposed to slavery and organised support for the abolition movement, so it is something that our region was very involved in.

Mark

So maybe, the third key thing about this period, I would say was the way in which the idea of democracy developed. So, at the early part of Queen Victoria's reign, it was really only very rich landowners and particularly out in the countryside who actually had a say in Parliament and what was happening in the Government. But, through different Acts in Parliament, particularly in 1832 and 1867, and as a result of struggles and demonstrations and protests by people such as the Chartists and in the later period, the Suffragettes, we got the expansion of the vote.

Although it was still - even by the end of the Victorian era - only men who could vote and only men with property that could vote, but it had spread to the towns and the cities. Then, at the beginning of the next century - after Victoria died - then there really was an expansion of the vote to the working-classes and eventually, to women as well.

Sheena

I believe we did a previous episode on that, didn't we Mark?

Mark

Yes - on the history of democracy, that was episode 4 of season 1 of the podcast. So, again, for those people who want to know more about that development of the vote and the struggles around that, you can find that, if you go back to that episode.

So, Sheena - tell us a little bit about Queen Victoria herself.

(8:47)

Sheena

Yes, Mark. Well, I've always been interested in Queen Victoria because I've seen statues and monuments and lots of lakes and mountains are named after her, so I've tried very hard to find out about Victoria, the woman. I know she was the first Monarch that travelled on the railway, which you mentioned. She was the first monarch to live at Buckingham Palace. She was Queen at 18, so a very young queen. And even though we had a large British Empire, she was very small in stature - she was somewhere between 4 feet 10 and 5 feet 2- lots of different descriptions of her height. But she was this very tiny person, but obviously very, very important.

She married, once she became queen. She married Albert, her first cousin and even though it was a very convenient marriage for Europe and for the UK, I think it was a love-marriage. I think she definitely was devoted to him and they had 9 children in total and they had 7 children in the first 10 years of their marriage, so a lot of the time Victoria was either pregnant or, you know, had a lot of child care to organise, even if she didn't do it personally, herself, and Albert played a very important part then in helping to run the country. He was very well educated and very efficient and I think that she was very happy that he took a role - really, he performed and behaved like a king, and I think she was happy with that.

(10:43)

Mark

Tell us where did Albert come from, Sheena?

Sheena

He was German. He was the Prince of Saxe-Coburg at the time.

Mark

And is that - why was that significant, do you think?

Sheena

I think it was important because Britain as a world empire, and Germany was an evolving, powerful country at the time, and even though they were cousins, first cousins, it was still important, because of the countries that they represented.

John

And as Sheena's pointed out, the element of dynastic marriages, is very important in Queen Victoria's life. Obviously, she married Albert Saxe-Coburg-Gotha and then many of their nine children went on to marry into the royal families right across Europe. So, the most famous example of this is the fact that, at the outbreak of World War I, Czar Nicholas of Russia and his wife Alexandra, and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, were all the first cousins of King George V [the fifth] of the United Kingdom, via Queen Victoria.

Also, Queen Marie of Romania and Queen Sophia of Greece, at the time, were cousins to King George V and this came ... this ended up giving Victoria the title of ... the unofficial title of "The Grandmother of Europe".

Sheena

Right - so that makes sense then, why, in 1914, they changed their name from "Saxe-Coburg-Gotha" to "Windsor", so that their name didn't sound as German.

John Yeah - because we were at war with the Germans and they didn't want a German- sounding surname, so they thought Windsor sounded a lot more English, so that's why the current royal family are known as Windsor.

Sheena

Just going back, domestically, to England and at the time, they were a very popular royal family and they ... the idea of Christmas - I think we've mentioned this before on other podcasts as well - that it was a German tradition and it became part of a British tradition, as well. So they were a very popular British family. And one of the things that's mentioned a lot about that time, is the morality of the Victorians. And sometimes they're accused of being very prudish in the way they behave.

They did things like Shakespeare and some of Shakespeare's stories were cleansed of anything that was remotely rude and the same with quite a few of the other classics. They stopped things in society, like "bull-baiting" and "cock-fighting", and things like that. So we became a society, maybe, with that stiff upper lip that people associate with the British, even now, I think, sometimes.

(13:58)

Mark

Well, I think one the things it's known for is a strict code of discipline, in the family. The phrase that was often known was that "children were expected to be seen but not heard". So children had to behave themselves but really weren't expected to have much fun or to actually interrupt anything that the adults were doing. Although to be honest, I think that was very much what it was like amongst certain middle-classes, because actually the children of the working-class were actually out working, most of the time. So that's very much an image I think of the more middle-class, but certainly, that idea of a very strict upbringing, certainly for middle-class children, I think is typical of the Victorian period.

Sheena

Yes - and lot of people were interested in Victoria's family. And, especially, I think the most important thing that happened was when Albert died, so suddenly and unexpectedly, at the age of 42, when he had still a young family and a youngish wife. He died, and there was shock for the Queen and for the country. So there was an an outpouring of grief towards this family, and then I think we remember Victoria, dressed in black, because she did that for the next 40 years. She never forgot Albert, she slept apparently, with an image of Albert next to her at night. His clothes and the hot water were prepared every day for 40 years, as if he were still alive.

Publicly, Victoria certainly was mourning the death of Albert. But something very curious, that I've found out, when she died: she was buried with her wedding veil in her coffin, but she had Albert's dressing gown with her in the coffin but apparently, she left secret instructions to also have a photograph of her Scottish servant, John Brown, who she had a very close relationship with, and also, apparently, in the coffin, was a lock of his hair and it is even said, she asked for his mother's wedding ring to be placed on her finger. So maybe there was some secret to Victoria's family life that we still don't know about.

Mark

Now John, you're going to tell us a bit about what was happening in Ireland at this time and why that's important to this period and indeed to what happened after.

John

Yeah - the main thing that we're talking about today is the period which is known - well, known in the Irish language as "an Gorta Mor" - so that's the Gaelic language which is spoken in Ireland. So "an Gorta Mor" means "the Great Hunger". So, most people when we're looking at history from an English point of view, it is known as the Irish Potato Famine. Because one of the reasons for the Great Hunger - and I've been looking at this, a little bit like - in modern terms, we've seen Covid, appearing in China - and then spreading through the world as people travel across the world, there was a thing at this time, known as the potato blight, which was basically a disease that effects the potato and it destroys the leaves and the potatoes themselves.

Now this had spread from North America: it spread to Europe, then through England and into Ireland. Now it caused a lot of deaths from starvation, across Europe, across England, Scotland but it was particularly severe in Ireland. Because the word we would use is ... the potato, it was the staple crop. So the vast majority of the people who lived in rural Ireland, were dependent on the potato. It was the main source of food and it was also the main source of income.

So from 1845, this terrible disease takes hold in the crop, and in successive years, there's a complete failure of the potato crop. Now for anybody who's been to Ireland, or watched Ireland on the television, or if you ever visit there: the idea of a famine, it seems hard to comprehend. Ireland is so fertile, it's green, it's lush, it's beautiful; there's cows, sheep everywhere, productive farms but that's what we saw - we saw famine, so the likes we might see today in Sub-Saharan Africa or in other places. We saw a really, really dreadful period of hunger and famine.

(18:48)

One of the reasons that this period of famine has been such a controversial period in history is that it's seen, and rightly so, as not being only a natural disaster. The famine itself eventually led to the deaths of a million people in Ireland: so 1 in 7 of the population, and up to 2 million people left Ireland forever. Mainly, to go to North America, many of them came to England, to Liverpool, Glasgow and other places. But the real controversy that continues, when we're examining this period of history, is that the Government at the time didn't offer anywhere near as much assistance as they should have done. So, initially, when the famine first began, a chap called Robert Peel, was the Prime Minister (very famous for setting up the police force in England, that's why we call police "bobbies" to this day, after Robert Peel ).

Now, he, basically did something very important. He repealed what were called the Corn Laws, so he took tariffs off imported food and he did start to import lots of food and distribute it to the people in Ireland, who were starving. However, he left power, he was replaced by a chap called Lord Russell who was, at that time, the leader of the Whig Party, who were essentially the forerunners of the modern Liberal Party.

Now the ideas that these people held at the time was something we call "laissez-faire" which was a French word at the time, but basically, they believed that you should not interfere with the economy. So if the people were starving; if there were shortages, the market economy would find a balance, and it would work things out and that Government interference in the economy was a bad thing. So they effectively left things to their own devices.

One of the other controversies is that during the period that people were starving, Ireland was exporting lots and lots and lots of food, so grain, oats, butter, pork, beef were still being exported to the Empire and being exported to mainland England, as well. So really, like I said, this becomes the key event in terms of modern Irish history, hugely important. Obviously, if you speak to somebody from Ireland about the subject, they'll be very knowledgeable about it, be able to talk to you about it, they'll know the history. It's kind of been brushed over, in terms of the English or the British approach to history. As I say, a key event in Irish history.

Basically moving on from the famine, we see obviously, the huge amount of people who leave Ireland. Ireland to this day, in Europe, is the only country whose population is smaller now, than it was in 1850, so you know you've seen a huge amount of people dying, and a huge amount of people leaving. It led very importantly, basically, to a rise of widespread nationalism in Ireland: so, the idea that Ireland should become an independent country. This developed through the later years of Victoria's reign.

So, in the 1870s and '80s, we saw what we call the "land wars"; so this was a period of agitation, uprisings, led by a group of people called the "Land League", so they were opposed to the Protestant British landlords. They were fighting for the Irish peasants, the native Irish people to have their own land and to have a political voice. And, eventually, this led on into the early twentieth century: the rise, as I say, in Irish nationalism, which came to a head during World War I, the rising of 1916, and eventually in 1921, the setting up of the Irish Free State.

An interesting language point: during this, the latter years - we just talked about the 'land wars' so the people who were fighting for their rights and fighting for the land in Ireland, they set up a system, whereby they would work against the landlords, so if a landlord was being particularly cruel to the people or extracting high rents, everybody in that area or county, would refuse to work for the landlord. The first landlord who this system was used against, was a man called Charles Boycott, so, to this day, the word in the English language, if you "boycott" something, it comes from the name of the English landlord in Ireland. A very interesting period - a very sad period but a period as well that was very influential, for the rest of the world.

If you look now at the United States, the current president of the United States: Mr Biden, is of Irish heritage, previous presidents, people like John F Kennedy, the Kennedy family, all from Irish extraction. I think some 30 million people - one of the largest ethnic groups in the United States, and all across the rest of the world - from Glasgow to Sydney, across New Zealand, Canada, America - everywhere you go, you will meet people of Irish extraction. As you will in Calderdale, myself and Sheena, we are both descended from the Irish people who moved to work in West Yorkshire.

Mark

And one of the things I've noticed where ever I've been on holiday, and I've been lucky enough to travel to a number of countries around the world, every major city has an Irish pub in it.

John

That's true. Yeah. Every where you go in the world, you'll find a Chinese restaurant and an Irish pub.

Language Support

Mark

This is the part of the podcast where I talk about a few of the words and phrases used in this episode. So today I'm going to start with the idea of "dynastic marriages". That's something that John mentioned, after we'd been talking about how so many of Queen Victoria's children married into the royal families of other European countries. So a "dynasty" is a succession of people from the same family who play an important role, in this case, in the running of a country, but it could be in, for example, the running of a business. So 'dynastic marriages' are marriages between families which create a more powerful set of relationships.

And Sheena talked about Victorian society - the Victorian age as being one that is often seen as "prudish". To be prudish is to be easily shocked by anything that's rude, and particularly, by anything related to sex.

And then Sheena also talked about the idea of Victorian Britain being a time when British people showed a "stiff upper lip". This is an expression that's been used - and is still used today - to describe British people. It means being determined in the face of difficulties, coping well with stressful situations. Now, that's the positive angle of it, but it's sometimes used more negatively: to suggest people who are a bit distant, a bit unemotional, that don't really show their feelings; that British people are a bit like that. Obviously, that's a generalisation, but it probably does originate from the Victorian period.

And then after the death of Albert, Queen Victoria's husband, we said that she went into mourning - now mourning is to express sorrow or sadness at someone's death and in many western societies, anyway, mourning often is associated with black - the colour black and dressing in black, which is what Queen Victoria did, for the rest of her life, after his death.

John talked about the tariffs that were introduced on certain goods. A tariff is simply a tax - a tax on certain goods, coming into or going out of a country.

And finally, John talked about the word "boycott" and just to explain that in a little bit more detail. If you boycott something, it means you refuse to have anything to do with it, so you could could boycott a business or a shop, or you could boycott a product, because, for example, you didn't think it was environmentally friendly; and John was explaining that "Boycott" was the name of one of the English Protestant landowners who many Irish people refused to have anything to do with.

That's it for this week. Thank you for listening - we'll be back again with you very soon. Keep listening for further information about the transcript, the website and the email address.

(29:15)

You can find the transcript - that's the written version of this episode - on our website:

www.staugustinescentrehalifax.org.uk

And that's where you can also find links to all the other episodes, and the transcripts, so you can listen and read along at the same time. That's also where you can find out how to donate, to help our work. We are a charity, supporting particularly, refugees, asylum seekers and migrants but also, all those in need in our local area and we would welcome your support, if you felt able to give it. If you follow on the website, the links to "Get Involved" and "Donate".

We also have an email address - that's englishforlifeintheUK@gmail.com

And we would love to hear from you - your thoughts on our podcast and ideas for the future.

We also have a Twitter account : @EsolSaint and there is additional material on that site.

I'll spell out all those addresses:

So, the website: w-w-w-.-s-t-a-u-g-u-s-t-i-n-e-s-c-e-n-t-r-e-h-a-l-i-f-a-x.org.uk

So that's the website.

The email is: englishforlifeintheUK@gmail.com

And that's "English for" spelt: f-o-r

And finally, the Twitter account: is : @ [at] [capital E] E-s-o-l- [capital S] -S-a-I-n-t

(Music)

All Podcast Episodes

The British Empire developed during Queen Victoria’s reign

Slavery was abolished in Victoria’s reign. William Wilberforce was a famous Yorkshire Abolitionist

Victoria and Albert were thought to have a perfect family life - they had 9 children

Queen Victoria was known as the Grandmother of Europe - so many of her children went on to rule in other European countries.

After Albert’s death, Queen Victoria wore black the colour of mourning, for the next 40 years of her life.

The Irish Famine

An Gorta Mor - The Great Hunger is remembered in memorials throughout Ireland

1 million people (12% of the population) died when the potato crop became diseased

2 million people emigrated to the U.K. and USA - today 30 million people in America are descended from Irish ancestors, including the US President Joe Biden.

The Irish Free State was declared in 1923, the majority of the Irish counties were now independent, only the six counties in the North remained part of the U.K.